Bookwriter

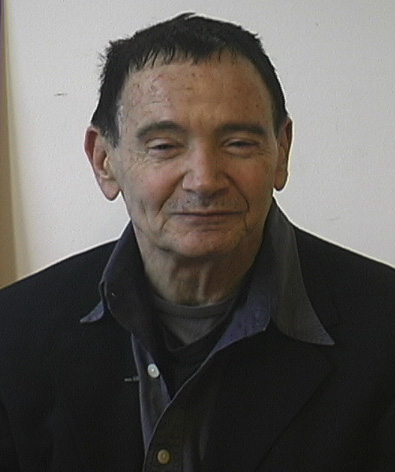

Allan Knee is on a roll. Granted, this roll started

well over a hundred years ago, but the popularity Allan enjoys today is based

on the universal themes of love, humanity and coming

of age that winds throughout his many works, as well

as the original works of his adaptations. In addition

to the decade he has spent adapting Louisa May Alcott's

Little Women to the stage,

Knee was also most recently the creator of the play

The Man Who Was Peter Pan,

made into the popular Oscar-nominated film Finding

Neverland.

ago, but the popularity Allan enjoys today is based

on the universal themes of love, humanity and coming

of age that winds throughout his many works, as well

as the original works of his adaptations. In addition

to the decade he has spent adapting Louisa May Alcott's

Little Women to the stage,

Knee was also most recently the creator of the play

The Man Who Was Peter Pan,

made into the popular Oscar-nominated film Finding

Neverland.

"I'm

proud of both of them," Allan smiles, when Finding

Neverland is mentioned. (He's too modest

to bring it up himself.) "They're both different

visions and yet they both have a great deal of heart.

If I can be proud about anything in my life, it's how

I've grown. I wouldn't say I was heartless, but I was

pretty closed off. And over the years I have opened

up. And when I see Little Women

or Finding Neverland, they're

like endorsements of my own opening up as an individual.

In some ways it doesn’t surprise me that they

both were released about the same time. How I got here,

I don't know, but I know it's where I wanted to go."

"I've

done a lot of adaptations," he adds. "I've

done The Scarlet Letter, I've

done Around the World in 80 Days.

What you try to do is, you have to be true to the soul

of the story, the essence of the story, the heart of

the story. If you're not identifying with the heart

of the story, then don't adapt it—adapt something

else."

Do I detect a trend, here?

"I

love the nineteenth century," Allan nods. "I

love nineteenth century New England, and I loved the

writers from the nineteenth century New England: Hawthorne,

Melville, Thoreau, and Louisa May Alcott. When I see

a writer like Jo March, like Louisa May Alcott, J. M.

Barrie, young Peter in Finding Neverland—these

are budding writers. These are people trying to accept

their own uniqueness. These are people struggling with

life, both in an emotional way and in a literary way,

and that encompasses me. That totally enrapts me. I

want to write about it, I want to explore it."

Allan sees the rites of passage from childhood to adulthood

as a critical moment everyone undergoes. Each of the

four March sisters must make this transition in her

own way—through marriage, through career, even

through death. But, Allan is quick to point out, there

are four men in the show, too, each going through his

own transition as well. They are a source of special

pride for him.

Allan especially identifies with Professor Bhaer, seeing

Bhaer's slow blossoming over the course of the show

as a mirror of his own gradual awakening. Of course,

he also sees himself in the ambitious Jo March, the

would-be writer and heroine of Little Women.

But surprisingly, Allan admits to another identification,

one that's "slightly embarrassing".

"I

adore Amy, the youngest March sister," he laughs.

"Amy's spoiled, the irritant, always wanting things,

always feeling she never has enough. Anyone who's a

younger sibling knows that feeling. You always feel

like, 'When's MY chance going to come? When is it going

to be for ME?'"

Clearly, Allan's chance is now, though he's so modest

and unassuming you might not know it to talk to him.

Any Amy-ish basking in all this recent attention is

not outwardly evident. Make no mistake, Allan is justifiably

proud of his accomplishments. But he is quick to point

out there are no shortcuts to success—only a long,

hard slog.

"I

have never given up," he says. "I've gotten

letters recently from friends who have known me twenty,

twenty five years, and they said 'I know how much being

a writer means to you, and you've never quit. And here

you are, on Broadway, and doing other things, and it's

just amazing.'"

"You

know, we're given one chance on this earth,"

he adds, half to himself. "Jo March knows

that. She doesn't want to waste it. I know that.

I don't want to waste my chance. I've always

dreamed big. I've taken it a step at a time,

but I've never allowed myself to quit. And I

still have tons of dreams. I'm still dreaming

big. It will never stop."

|